- Home

- About VCI

- Testimonials

- Contact Us

- Adventure CE

- VCI Programs

- VCI Ethical Values

- VCI Consultants

- Trusted Colleagues

- Initiatives to Watch

- Publications

- S@S Proceedings

- Design the Dream

- Veterinary Medicine & Practice

- Beyond the Successful Veterinary Practice

- Building the Successful Veterinary Practice, Volum

- Building the Successful Veterinary Practice, Volum

- Building the Successful Veterinary Practice, Volum

- Design Starter Kit for Veterinary Hospitals, 3rd E

- Healthcare of the Well Pet

- Promoting the Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Prac

- Veterinary Management in Transition

- Veterinary Healthcare Services

- Veterinary Practice Management Secrets

- Newsletters

- Fortnightly Publications

- Fortnightly Articles

- Monographs

- Cat Sighting

- Pet Parent Sites

Veterinary Consulting International

(303)277-9800

www.drtomcat.com

|

Click below for the PDF's of the Fortnightly Articles or scroll down to read on current page:

November (mid-month) - Debate & Strategic Interactions October 2014 (EOM) - Zoning Concepts October 2014 (mid-month) - Patient Advocacy September (EOM) 2014 - Marty Becker Fear Free September (mid-month) 2014 - IQ vs EQ Leadership September 2014 - Program-based Budget Planning August 2014 - Family = HAB July (mid-month) 2014 - Beyond Problem Solving July 2014 - Veterinary Practice Images June 2014 - Multi-generational Team March - end of month- 2014 March - mid month 2014 End of January/Beginning of February 2014

September (mid-month) 2014

IQ vs EQ LEADERSHIP

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE

Diplomate, American College of Healthcare Executives

Veterinary Consulting International

DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com

In his 1996 book, Emotional Intelligence, author Daniel Goleman suggested that EQ (or emotional intelligence quotient) might actually be more important than IQ. Why? Some psychologists believe that standard measures of intelligence (i.e. IQ scores) are too narrow and do not encompass the full range of human intelligence. Instead, they suggest, the ability to understand and express emotions can play an equal if not even more important role in how people fare in life.

What's the Difference Between IQ and EQ?

Let's start by defining the two terms in order to understand what they mean and how they differ. IQ, or intelligence quotient, is a number derived from a standardized intelligence test. On the original IQ tests, scores were calculated by dividing the individual's mental age by his or her chronological age and then multiplying that number by 100. So a child with a mental age of 15 and a chronological age of 10 would have an IQ of 150. Today, scores on most IQ tests are calculated by comparing the test taker's score to the scores of other people in the same age group.

EQ, on the other hand, is a measure of a person's level of emotional intelligence. This refers to a person's ability to perceive, control, evaluate, and express emotions. Researchers such as John Mayer and Peter Salovey as well as writers like Daniel Goleman have helped shine a light on emotional intelligence, making it a hot topic in areas ranging from business management to education.

Since the 1990s, emotional intelligence has made the journey from a semi-obscure concept found in academic journals to a popularly recognized term. Today, you can buy toys that claim to help boost a child's emotional intelligence or enroll your kids in social and emotional learning (SEL) programs designed to teach emotional intelligence skills. In some schools in the United States, social and emotional learning is even a curriculum requirement.

So Which One Is More Important?

The above example gives you some idea, and in many cases, veterinary school logic prevailed (‘A’ students will end up working for the ‘C’ students after graduation since “A” students have very little client rapport capability). From an academic point of view, IQ has been viewed as the primary determinant of success. People with high IQs were assumed to be destined for a life of accomplishment and achievement and researchers debated whether intelligence was the product of genes or the environment (the old nature versus nurture debate). However, some critics began to realize that not only was high intelligence no guarantee for success in life, it was also perhaps too narrow a concept to fully encompass the wide range of human abilities and knowledge.

IQ is still recognized as an important element of success, particularly when it comes to academic achievement. People with high IQs typically to do well in school, often earn more money, and tend to be healthier in general. But today experts recognize it is not the only determinate of life success. Instead, it is part of a complex array of influences that includes emotional intelligence among other things.

The concept of emotional intelligence has had a strong impact in a number of areas, including the business world. Many companies now mandate emotional intelligence training and utilize EQ tests as part of the hiring process. Research has found that individuals with strong leadership potential also tend to be more emotionally intelligent, suggesting that a high EQ is an important quality for business leaders and managers to have.

So you might be wondering, if emotional intelligence is so important, can it be taught or strengthened? According to one meta-analysis that looked at the results of social and emotional learning programs, the answer to that question is an unequivocal yes. The study found that approximately 50 percent of kids enrolled in SEL programs had better achievement scores and almost 40 percent showed improved grade-point-averages. These programs were also linked to lowered suspension rates, increased school attendance, and reduced disciplinary problems.

Observations

So what does it mean in a veterinary practice?

If you refer to the table above, you can see characteristics/traits of a successful leader on BOTH SIDES of the equation. The challenge is we select veterinary students based on IQ, and the years of school work hard at eliminating any EQ traits. EQ is client relations, EQ is staff empowerment, EQ is charisma! The journals are filled with IQ data points, as are our Association conferences and webinars. Contemplate this, what is more IQ than a webinar where you cannot read body language? Our downward spiral into IQ nirvana is becoming a slippery slope.

The charismatic veterinary leader makes mistakes and learns from them. Yet in veterinary schools, we increase the fear in students by 25% based an intimidation culture which has been present your eons. The fear of failure is ingrained in students before graduation, so learning from mistakes is NOT a cultural expectation in this profession. That makes incremental change scary but required. It also makes safe harborage for mundane factors like comparing Gross Turnover, the Average Client Transaction or expense percentages, three factors that have an UNKNOWN NET INCOME influence.

What would happen if a practice would compared lost clients to new clients each quarter? Where would the operational focus be shifted? An easier factor would be pharmacy income compared to pharmacy expense each month; yet most Australian practices still look at ‘Cost of Goods Sold’, which disguises line item comparisons such as pharmacy net income. Why would any logical person combine surgical supplies (zero mark-up), with nutritional supplies (30-35% mark-up), with pharmacy resale (~ 2x mark-up), with laboratory (50-100% mark-up), with DR Imaging (almost pure net), and consider it a rational comparison factor?

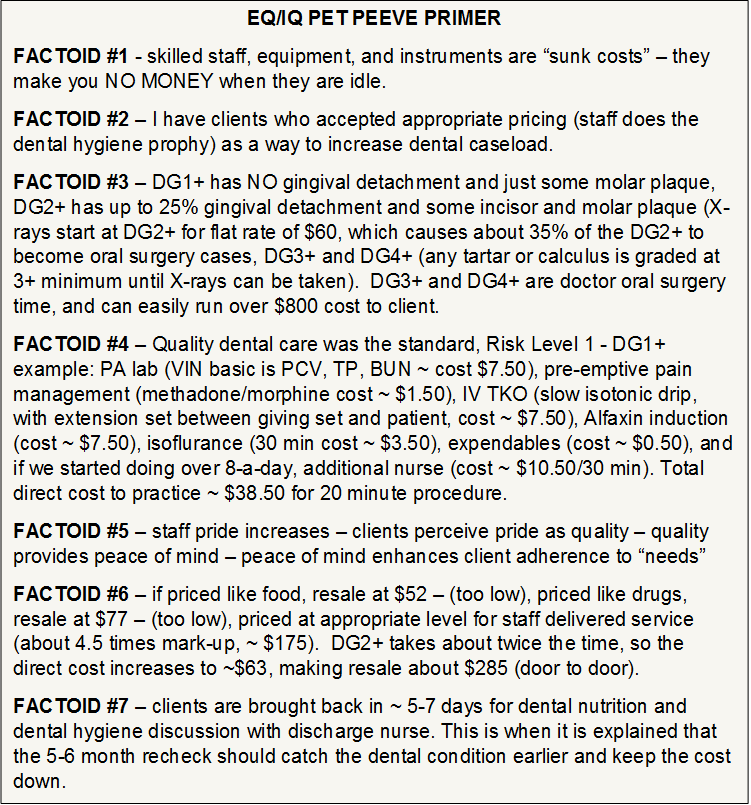

What would happen if a practice would compared dental cases booked to total patients seen during the month (dental specialists tell us 85% of adult animals have some dental need)? What would happen if a practice would compared nutritional referrals to veterinary nurses to number of patient seen (surveys show us that about 50% of adult animals have some prescription diet need)? All DG2+ mouths deserve dental X-rays, yet there are still veterinary practices without dental X-ray, or is they have one, are using it by exception. POINT – if the DR dental X-ray series is about $55-$60, regardless of number of images taken, and assuming they are taken by staff members, about 30-40% will become Oral Surgery (DG3+ and/or DG4+) . . . the secret is to keep the entry level dental care (DG1+ and DG2+) reasonably priced (i.e., appropriate pricing for staff delivered care).

Sure, our practice management software cannot give us this data easily. But why not? The basic business formula is “Income – Expense = Profit”, yet our veterinary software vendors say “sorry, can’t do that”, and we accept it. Why do we accept mediocrity?

Almost every practice owner and manager can give you the average expense % for common categories, but very few know the offsetting income center and/or expected profit margin for that line item. Think about it – Average is the best of the worst, or the worst of the best – it is the number in the middle – it is mediocrity.

This mediocrity continues into staff empowerment. Sure, most of us have seen dentists working with a 10-16 column per dentist appointment log, to allow for hygienist and whitening appointments. We have seen our physicians operating with medical assistants and nurses, with multi-consult rooms per physicians. And this year, the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) has declared 2014 to be the year for “team-based healthcare delivery”, yet I published the 500 page text with this title in 2008 and placed it in the VIN Library for free download.

THE PRACTICE SUCCESS PRESCRIPTION:

TEAM-BASED VETERINARY HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

//www.vin.com/Proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=TomCat2007&O=Generic

So, EQ is often right and IQ is often right. The reality is that the mix is needed. There are volumes now being written about mindfulness and happiness. These factors appear pro-EQ and contrary to IQ, but in the real world, it is all about team harmony and self-actualization (thank you Abe – Maslow that is).

You would think those with a high IQ would be looking for a savvy veterinary-specific consultant to facilitate their migration from yesterday to tomorrow, but it is the short-term thinking aspect of those with high IQs that often derails that engagement. I just came out of a practice that was floundering and stressed a year ago, yet after a year of consulting, they had harmony, liquidity and a 54% practice growth. Sure, that is an exception, but it is possible (e.g., 11 to 38% is the usual range of growth when the team is committed and the leader is willing to change)!

September 2014

PROGRAM-BASED BUDGET PLANNING

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE

Dipomate, American College of Healthcare Executives

CEO, Veterinary Consulting International

DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com About the time we can make the ends meet, somebody moves the ends. Herbert Hoover, 31st President Before we start, please understand, I don't see budgeting as an accountant's exercise. We publish a VCI Signature Series monograph, Fundamentals of Money Management, which differentiates between tax accounting and managerial accounting (it includes a Chart of Accounts diskette compatible with QuickBooks, by Intuit). I see program-based budgeting as activity and program planning for the coming year; it is a series of healthcare delivery commitments by the practice doctors and staff. The cash budget is only a series of clinical programs to which we have historical data on the income or expense impact on any practice. A good leader promotes income development activities and allows his/her team to increase net by controlling expenses and extending the healthcare delivery programs beyond the professional diagnostician. Therefore, the annual budget cycle includes, in my mind, the annual marketing plan and the communication/training plan for the team, as well as commitment to higher levels of quality healthcare delivery. PROGRAMS = NET INCOME More veterinary practice owners are learning that a focus on the front door is good business; they know when their procedures are down. A good program-based budget provides the needed measurements for growth; how many procedures are we doing, and what are the relationships to each other (e.g., dentistries to outpatients, fluids to surgeries, etc.). These measurements are essential to make success happen; it is also called have standards of excellence in the practice’s healthcare delivery habits. In the 1998 ISUP text, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Programs & Procedures (Volume 2), Chapter Four, and Appendices D, E and F, examples are provided that most any practice can follow to build a monthly cash budget, establish effective Income Statements, and build upon an established Chart of Accounts (the Chart of Accounts in Volume 2 expanded the AAHA system to include more income centers). Mechanically, the income statements of the practice should reflect the major income categories produced by the practice’s veterinary software at EOM, and those major categories are then used for the top left-hand column of the budget instead of "sales", and the income history of the last three years can be used to determine the average earning power of each month (percent of annual income). But the chart is not the planning process, and the planning and projections are what is needed to make it happen. CONTROLLING CASH FLOW The traditional approach to restrict expenses and inch the prices upward is adequate to maintain average growth to defend against inflation, but it does not promote expansion. The cost of professional services continually rises as do the fixed and variable costs. It is one thing to project an increased income for next year; it is far more difficult to cause it! The secret to obtain those extra degrees of expansion (practice growth) is based on the increasing horizontal (adding services) and vertical (expanding existing services) levels of income available to the practice. Income production (new or expanded services and products) is the major variable in controlling liquidity, also called "cash flow" by some. To control (or monitor) income levels, fees must be projected and cash must be received (and bad debt must be minimized). We will assume the practice has a clear set of values and core competencies, a future-based vision, and a CONSISTENT practice philosophy in place (an accepted core platform of services and products). This is started with a cash budget, with paired income and expense centers where possible, projected by month, for the coming fiscal year (see the 1998 ISUP text, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Programs & Procedures (Volume 2), Chapter 4, Program-based Budgeting):

Controlling the cash flow means knowing what is expected then measuring the accomplishment of that performance level. The program-based budget must be compared to actual performance on a monthly basis and adjustments need to be made in the remaining monthly targets if the year end goals are to be met; this is often done in dollars, but when variances occur, you must look at procedure counts or you are just fooling yourself. As I was surfing the net (AOL and NOAH), I watched veterinarians discuss their 1998 increase in gross, the percentage of gross which was due to vaccines or dentistry, and other such “first liar loses” type discussions. When are we going to learn? THE FRONT DOOR MUST SWING

The secret is what makes YOUR front door swing, Every practice has a different formula, but there are common components, and they are called programs (as in program-based budgeting). We realize that a pre-anesthetic laboratory screen is REQUIRED in virtually every case (although the intensity and scope varies), and as stated in a recent Nevada State Board letter, 80 percent of the surgery cases should have fluids running. (When was the last time you took a fluid therapy refresher for CE?). We have stressed the grades of dental conditions, and recording of the grades in the medical records, to the point where those doing it have doubled their income. We even have a Colorado practice who has contacted Dr. Marv Samuelson (VARL) for assistance to develop dermatology as an income center program (e.g., even in Colorado, 15 percent of the dogs coming in the front door have atopy). But let’s go forward with fundamentals and see what you are taking for granted, especially in surgical cases. We know in our hearts that pre-anesthetic blood screening is essential . . . one State Board has publically informed every practitioner in the State that 80 percent of surgery cases should be on fluids . . . we read about pain management, and listen to seminars, yet believe clients can make a knowledgeable decision about pain management with no training - post-surgical pain killers are not optional - everyone knows PAIN IS INHUMANE! Yet every day, there are practitioners putting animals at risk, and themselves into liability, by practicing wallet medicine instead of quality medicine. How about radiology? Fact: most every practice has forgotten that a radiographic baseline of the thorax is good medicine. A boarder who is coughing does not always have kennel cough. Dogs do have other problems. For instance, a negative Difil test tells you about circulating microfilaria, not adult heartworms in the thorax. Current literature shows that some of the coughing cats previously diagnosed as asthmatic are actually heartworm infested, even in non-endemic areas. ONLY an X-ray can do this effectively. Consider this: Dr. Bob Smith (radiologist, University of California - Davis) believes that dogs with a negative OR positive heartworm test still deserve a thoracic X-ray series before starting the preventive care or treatment protocol. Moving on to the abdomen, when was the last time you did an IVP or cystogram? There are more things than just foreign bodies occurring in the abdomen. Have you ever considered the diagnostic advantage of a Baro-spheres when doing a laparotomies, since leakage is not a by-product of these pellets? During a short course recently held, it was stated, “Use of the Penn Hip technique to aid in the diagnosis of hip dysplasia and the introduction of Baro-spheres for barium studies have proven diagnostic advantages”, and one of our clients attended and KNEW he could go back to practice and virtually double their income in this area. Look at the advances in cardiac evaluation. The handheld ECG which gives a lead-II rhythm strip can be used with every annual life-cycle consultation (yes, I know you call it an annual exam, but which sounds more accurate?). The handheld ECG is economical enough that if it was used for each “annual”, at a fee of $2.00 additional, it would be totally paid for in less than six months; then it is a NET-NET program every time it is used! The use of echocardiology is on the rise; within five years most quality practices will be using it regularly. This modality is technique-driven and relatively easy to read; the difficulty lies in determining where and how to place the transducer. As Dr. Larry Tilley states so often, “Telemedicine now allows a practice to be in contact with a specialist - even across the country - within minutes”. Reflect on the blood pressure diagnostics of your practice. It cannot be emphasized enough. Every practice should be using a blood pressure device daily (e.g., Doppler). We have some practices which ensure that the feline blood pressure monitoring is part of the annual life cycle consultation. It has been shown that 60-plus percent of the cats in renal failure can have hypertension. It has also been shown that hypertension can be manifested in such unusual signs as anisocoria. Dr. Mike Garvey (AMC, NY) has stated that blood pressure measurement is paramount - for more than hypertension . . . up to 30 animals die every day from hypotension for every animal that dies from hypertension. ECONOMICS 101 ALA DR. TOM CAT “Tom Cat, we will damage our relationship if we add these unneeded diagnostics.” You are right, if they are unneeded. But in every case stated above, there was a medical need. The fact that you have taken radiology for granted means the overhead is still larger than the income from the program center. Yes, program center -- not income center, not profit center. The front door swings because we believe in our health care programs and share that conviction with clients as NEEDS for their animal(s). If you don’t medically believe it is needed, NEVER do it! And for those of you who take one film to “save the client money”, remember what every text and radiologist has stated, “If it looks like a duck, sounds like a duck, and walks like a duck, it must be considered a duck . . . and ducks state very clearly, QUACK, QUACK, QUACK!” If radiology is needed, two views are needed. To provide half the care is a violation of professional ethics and the Practice Act. Think of lameness cases where you have said, “If this does not get better, we may need to take radiographs”. The client brought a suffering animal to you because they wanted “PEACE OF MIND”, and you only offered them “tincture of time”. And you wonder why they never come back? Lameness generally requires radiology to determine the appropriate treatment as well as the prognosis, and in client relations, they came to you because you are the diagnostician! The ability to believe in good medicine is the cornerstone of a successful practice. The ability to convey this need to clients is the cornerstone of a profitable practice. The overhead of a veterinary practice is pretty fixed (in well managed practices, less than 50 percent of the gross income is spent on monthly P&L expenses, not counting rent, doctor monies, and ROI benefits (quarterly rate stays below 48%). So, it is the delivery of services and products within existing staff and facility capabilities which can make the net income difference. TODAY IS THE FIRST DAY OF THE REST OF YOUR LIFE We really don’t care what you have already done; that is past. What we care about is what you are willing to do. Every year, new continuing education courses mean you have the opportunity to enhance practice programs. The continuing education experience which does not add one new program per day of CE attended was a wasted expense. The new program is designed to provide better care, and there is a value associated with that client benefit. That value, as assessed to clients, should be reflected in your program-based budget for the year. The cash flow reports from that computer in your office ONLY reflect the “belief level” of the providers in the new program(s) being offered. The choice is yours, we are here to help, but the belief starts in your gut and ascends to your heart. When your heart believes in the program, the clients will accept the care as needed and essential. It is your choice -- lower the net each year, or provide better health care delivery programs.

JUST DO IT!

THE PRACTICE BUDGET TEAM The control of the cash flow from programs that match the core values of the practice is a team responsibility and as such, the plan must be a team effort. The practice budget team should include the practice owners, bookkeeper, office manager, lead technician, lead receptionists, and an outside mentor. The technician and receptionist should be involved in those areas where they have a first-hand interest and impact but need not be involved in all parts of the team planning. The outside mentor can be a CPA, consultant, attorney, or psychologist. To be most effective, they must be detached from the practice's patient healthcare plan. To be most effective, this entire day of isolated planning sessions is without spouses. The spouse, as with any client, usually has a hidden agenda and will muddy the team effort, even if just to wait on the sidelines for a meal companion. It would be appropriate to form focus groups of respected clients to discuss potential healthcare service opportunities before the off-site planning session. After the budget planning session, this type of client-centered input may be counter-productive to the success of the plan. The budget planning team needs a playing field (established rules and historical game experience), and that is usually the past financial statements. The planning team needs to meet at an off-site location about three to six months before the fiscal year begins and use the historical data to develop a strategic plan for the practice's cash flow. To be most effective, the practice manager becomes the meeting coordinator and handles all the following:

a) For the key team members (owners, practice manager, and CPA or bookkeeper), possibly with a mentor, start at 7:33 a.m. with a very light breakfast (the mind works better on a lightly filled stomach), coffee, tea, and juice.

b) At 7:57 a.m., start review of the previous financial statements using an overhead projector so all can see and discuss the key elements (view graphs prepared of previous fiscal year, all twelve months, of the income statements and balance sheets).

c) Have a practice cash budget outline prepared using percentages per month per element of income or expense, as available, for handout after the historical review and before brunch.

d) With the arrival of the adjunct team members (associate doctors, lead receptionist, and senior technician), provide a light brunch at 10:37 a.m. e) With the expanded planning team, start a review at 10:56 a.m. of the projected program-based budget percentages that were developed from historical data on the previous practice team performance and client utilization habits, and brainstorm which programs can be added or expanded in the next fiscal year (don't kill a single idea during this brainstorm, just write them down and tape them to the wall).

f) At 12:30 p.m., break for lunch on-site, resume at 2:04 p.m. to develop expected income per program area of interest to support cash budget. This is often where the "reality check" is provided by the nurse technician and client relations receptionist to mediate the "grand ideas" of the key team. Human resources are only so flexible and expandable, and these two persons must stand up for the quality of life of the staff. Pros and cons, alternatives, and methods to reach the "grand ideas" need to be the target of the discussion, but it may require adjusting the personnel budget, equipment budget, or even the facility size.

g) Soda, juice, coffee, and tea break at 3:31 p.m. Key staff rejoin at 3:47 p.m., but without CPA/bookkeeper, technical assistants, and receptionist (released for remainder of day).

h) Resume with emphasis on new business areas, marketing potentials, and client acceptance factors. Extra expenses (e.g., training, space, equipment) to support new income areas need to be explored in detail. Compromises will now be required based on the input provided by the lead nurse technician and receptionist coordinator. At least 60 percent of their ideas need to be incorporated to have the budget be perceived by the team as realistic and a useful process.

i) Supper break at 5:45 p.m. for two hours, time to relax and unwind. Attempt to stay away from excessive food or drink indulgences, since there is still work to do.

j) Rejoin at 7:46 p.m. for a "wrap and polish" session of all that has gone before, to expand on core competencies, core values, and practice philosophy applications. Ensure you include a staff impact assessment and communication plan. This may include an additional training budget. Also center on those portions which were provided by the technician and receptionist that could not be used, as well as the changes that will be needed to make the annual program a success. The need for the communication plan is critical for two elements: the paraprofessional staff and the clients. A draft transition plan, a month-by-month sequence of changes or additions for the next year, would be an appropriate and organized method to communicate the decisions of the budget planning process. This plan should integrate all the different plans, and ensure that no member of the staff would be tasked with more than three new functions/habit changes per month.

MINIMUM BUDGET DISCUSSION ELEMENTS

The syllabus and the refined agenda discussed above need to contain certain elements, including: equipment, debt retirement, quarterly financial comparisons, cash outflow discussions, receivables, bad debt allowance (less than 1.5 percent), charity at the exam table (less than 3 percent of gross), employee discounts (less than 20 percent without IRS complications), tax laws, space potentials, computerization upgrades, people allocation per area (based on gross, with quarterly targets, such as 8.5 percent technicians, 7 percent receptionists, 2 percent kennel, 3 percent administrator), and finish with a fee schedule that supports the budget for people and equipment upgrades. Key financial and operational relationships need to be discussed, to determine indicators that management can observe to easily monitor trends on a monthly basis. Examples would include, but should not be limited to:

Some ratios, like the "Pharmacy Sales to Diagnostic Sales" by veterinarian, is a very individual ratio, but centers the doctor's attention on what they can do for the quality of care provided by the practice. Many of these can be graphed for more clarity when evaluating trends. In the ISUP text, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Programs & Procedures (Volume 2), there are eleven graphs and two charts in the Appendix for watching “the tips of the practice iceberg” on a monthly basis - we call it a dozen dots a month, although it is a baker’s dozen (13)! These are indicators to watch so you know when to look deeper into the operational trends or fiscal management of the practice.

Beware of the easy factors so often published without "the rest of the story", such as average client dollars per transaction (ACT). The ACT is often counter-productive since it centers attention on the wrong thing. What is the "computer's definition" of a transaction; is the ACT reported by veterinarian or by hospital; what is the over-the-counter sales impact; what is the income per inpatient visit versus outpatient visit; what are the payroll hours per transaction; what is the return rate per year (client or patient)? Some consultants demand that the square footage of the practice be used to compute cost centers, but the allocations of circulating space makes potentially profitable areas appear worthless. Evaluate services within the resources available to the practice and maximize income from each cost center. The bottom line of fee structuring is simply, if you are within about 10 percent of the community high, variances from national norms are not significant for the clients who seek quality veterinary healthcare services! The veterinary computer systems of today are designed to give abundant "data". This most often is minimal "information" for management decision making. A savvy practice manager must be able to take the information available and process it into knowledge that can be used for the good of the practice. In any practice, less than 30 factors are needed to reveal the monthly trends. In the area of laboratory services, expenses should be tracked by in-house versus commercial and income should be tracked by preventative, pre-surgical, and medical support functions. The examination/office call (better called "doctor's consultation") should be tracked by rechecks, normal, and extended consultations. In a healthy, mature practice, monthly operational expenses, without the major variables of rent, DVM salaries or return on investment (ROI), would be expected to be between 45 percent to 48 percent of the gross. The AAHA Chart of Accounts, expanded in the ISUP text, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Programs & Procedures (Volume 2), provides an easy access and comparison to the regionalized database of the profession. Quicken or QuickBooks (from Intuit) are excellent software systems for expense summaries and accounts payable needed to support the Chart of Accounts. Comparisons could include: outpatient drugs and medical supplies versus inpatient drugs and medical supplies, vaccination income as a percentage of gross, hospitalization income, X-ray income compared to expenses, over-the-counter sales, nutritional sales of prescription versus other products, boarding fill rate, baths per transaction, or the eleven fiscal charts provided by Catanzaro & Associates, Inc. Other expected ratios include rent at one percent per month of the fair market value (triple net lease), DVM wages (owner(s), et al) at 18-23 percent, CPA and legal fees at 0.8-2 percent, office supplies at 1.4-2.2 percent, or maintenance costs of 0.5-1.5 percent. In more progressive practices, healthcare parameters such as ECGs per thoracic X-ray or kidney dysfunction laboratory profiles per six-years-old or older canines examined are monitored since they relate to income potentials. MANAGERIAL EFFORTS Using the practice team to keep the budget plan on track will be enhanced when the accurate data is shared in a timely manner, using a format that is user friendly. Remember, the staff knows how much a practice takes in each day (they close out the computer), they just don't know what the costs are in most cases. The team which is used to keep the budget on track will provide feedback which will show the benefit of the time taken to make the information readable. The practice management methodologies required to make the budget plan happen is as simple as driving "A TRUCK", or in easier terms:

A = accuracy of data

T = timeliness of data availability

R = reformatted as information

U = user friendly

C = control cost of capturing data

K = keep on track monthly

The use of a posted "Dinner Bell Chart" (Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Programs & Procedures (Volume II), Appendix), helps the staff see the monthly income participation. It is simply a graph with appointment days on the horizontal axis and income on the vertical axis. The target line (done in highlighter) starts each month at zero and ends at the cash budget projection for that specific month. The daily gross receipts are posted on the chart at the end of each day, in a cumulative fashion ($1860 on day one, then $1435 on day two, would put the day two dot at $3295). The gross income dots are connected in dark ink each day. At the end of the month, if the dark line is above the highlighter line, the owners take the staff to dinner. While at dinner, the dinner site of the next Dinner Bell Chart celebration is chosen by the staff. If the cost of the site selected seems excessive, the owner simply adds that to the target before announcing the cash projection figure for the next month. As an added benefit and team builder, each third Dinner Bell success celebration should include the families or significant others of the staff members. They make the practice success sacrifices, too. When the staff centers on offering the services each animal needs (or the practice needs for professional healthcare decisions), the income should take care of itself. This statement is based on four assumptions:

1) that caring practices only "sell" peace of mind -- they give the client two "yes" alternatives which they are "allowed to buy" to meet the needs stated;

2) that the veterinary practice environment for horizontal and vertical diversification has been developed;

3) that it is well understood by the staff and healthcare providers; and

4) the team has been appropriately trained in both competencies required and client communication techniques.

These four assumptions are easier said than done, but that is the art of management rather than the science of accounting. The program-based budget is a system based on quality care, client-centered service, and patient advocacy . . . the accountant’s propensity for stating the obvious with an expense-based budget must be left in the past as lessons learned . . . the future is in making the front door swing, more times for your existing clients.

August 2014

FAMILY = PET BOND = PROFIT

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE

Dipomate, American College of Healthcare Executives

CEO, Veterinary Consulting International

DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com

HAB = human animal bond = the interaction of people and animals in our society = profit center of the future.

A majority of veterinarians make their living because of the human-animal bond, yet most veterinary practices do not capitalize upon the potentials available. The client calls the veterinarian because they have a concern about the well being of their animal and want an expert to assist them during their stressful decision time; they want peace of mind. The basic premise which needs to be taken when the phone rings is that “the phone shopper” wants a quality-based, caring veterinarian at “an affordable value”. A phone “emergency case” wants to be told they have done the right thing by calling and should come into the practice. No client who calls wants to be told to stay home.

The contemporary pet programs such as active pet selection assistance (AVMA©), pets by prescription and the Pet Partners© certification program (Delta Society©), Prescribe Pets Not Pills (VPI Skeeter Foundation©), and behavior management (AAHA©) promote the human-animal bond while supporting the healthcare reverence for life and quality of care programs. Many Veterinary Teaching Hospitals are starting telephone “hot lines” for pet owners to allow the students who volunteer to better understand the stress of animal stewardship grief and stress. A multi-faceted, interdisciplinary group, sponsored mainly by Hills, named VetOne©, started publicizing the family-pet-veterinary bond at major veterinary meetings and in our media as we entered the new millennium. The text, Promoting the Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Practice, was released in May 2001, and the second edition was published by the VIN Press in 2009 with a new well care chapter; it has 26 appendices of practical application programs. HAB information abounds, but practice commitments vary.

Definition of BIOETHICS: applied ethics to real-life, day-to-day problems of ethical decision making in health care delivery.

In the past, veterinary ethics have been forensic (legal) values we used to describe the professional approach to veterinary practice, but bioethics are the values we use personally in practice. Sometimes the veterinarian is the person who makes the bioethical decision, sometimes it is the person answering the phone, and on some occasions, it is the person who observes the suffering inpatient in a cage. But more often, the decision is laid at the feet of the lay people we come into contact with -- family, clients, public officials, judges, humane societies, and others. There is seldom any clear bioethical solution. Rather, there needs to be an awareness of its existence within the veterinary practice environment.

CHOOSING A THERAPY WHEN DOCTORS DISAGREE

This situation presents a wide array of ethical issues. Whether or not the client should be informed of the nature and prognosis of the illness is certainly pertinent, but is hardly the most significant question in the bioethics at hand. Attention should be focused upon a cluster of three basic ethical questions raised in this case:

The option to be chosen in each of the above three questions is not just a medical decision based on scientific training, but rather, a professional value judgment. When a healthcare team is being developed, these cases deserve a full staff discussion so the professional logic, subjective feelings, and practice core values become established so others can make similar decisions in the future.

ACTIVE EUTHANASIA

The American Medical Association states that active euthanasia is illegal, but they only deal with one species of animal. Exactly what are the fundamental measures of animal value and worth which require the veterinary bioethics to be evaluated?

The alternatives in euthanasia are generally not based in veterinary science. They are based in personal value systems and practice philosophies. In many of the practices we support, we suggest a “pain” versus “suffering” discussion when the patient is entering the golden years, when there is malignant oncology present, or other debilitating or chronic syndromes. Be proud that we can treat pain in many ways now; many clients do not know this. Suffering on the other hand, is often a subjective value observed by the client, including the animal soiling its den (urinating or defecating uncontrollably at home), bumping into walls due to poor eyesight, inability to maneuvering stairs, snapping at the children when startled due to loss of hearing, or similar behavior challenges. We spend the extra client time ensuring they know that we can “treat pain”, so they need to call whenever it seems to be present, while in a case of “suffering”, the client must tell us when the love of the animal outweighs the loss of the companion, and it is time for euthanasia.

ANIMAL ABUSE OR NEGLECT

This issue is sad but raises no difficult questions of principle at all. If there is a violation of the Animal Welfare Act - Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 9, Chapter 1, Subchapter A, there is neglect; if the act was intentional, it is usually considered abuse. Presumably in these cases, the individual or the family who has support responsibilities for the animal(s) is deemed inappropriate to the animal's welfare. But the veterinary practice which makes the decision to elevate the issue to the authorities must face bioethical issues.

When a practice promotes behavior management services, starting with house training, the incidence of neglect decreases in the clientele. Most clients are unaware of proper animal care, since they learned from their parents, who in many cases either came from the farm, or had parents who came from rural America, where farm dogs and barn cats had to fend for themselves. Like parenting, there are very few prerequisites in our family stewardship system, so if we do not do it in the veterinary practice setting, no one will. This is a wonderful area for staff bonding with clients, and the brochures and literature from AAHA make a great starting point, along with the appendices of the above mention text, Promoting the Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Practice.

THE KEY QUESTIONS

It is often said that issues of bioethics fall into two categories: some concern procedures for decisions, others the substance for decisions. The distinction, while intuitive, is not easy to sustain. How do we know which values should be followed unless we know what values should to be sought?

In biomedical ethics, there are usually five basic decision-making agents that require consideration by the veterinary practice:

There is a traditional adage in medicine, that is, "First, do no harm". In the previous bioethical issues, some would feel that the solutions were clear and definitive, that ethical issues do not exist. The areas discussed are illustrative of veterinary medical situations where there is room for reasonable people to disagree. The reason for this discussion was to make the concept of ethics in biomedical decisions become a reality, to show that bioethics do apply to veterinary practices, and to offer the opinion that bioethics should be an element of the decision making process in quality health care delivery in the veterinary practice.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL BOND

The American Veterinary Medical Association developed and has available all the documents and aides needed for active pet selection assistance by veterinary practices, including some very well done color brochures. The AVMA also introduced the Lost Pet Kit over a decade ago, yet many practices have neglected to integrate it into their practice programs; with digital photography, it is easy and takes very little space! The Delta Society has developed the protocols for Pet Partners and pets by prescription within the community and school environment. Either of these programs can develop new pet owners, clients who are already bonded to the practice since they selected their pet with the expert assistance of the veterinary professionals of that facility.

Human-animal bond resources are available at almost no cost to the veterinary healthcare facility. There are multiple human/companion animal bond (H/CAB) programs available from associations and other non-profit organizations, and 26 are listed in the appendices of Promoting the Human-Animal Bond in Veterinary Practice. The international clearing house for interdisciplinary HAB groups and programs is the Delta Society (800-869-6898). The American Veterinary Medical Association (708/925-8070) has the pet placement handouts and information as well as hosting the American Association of Human Animal Bond Veterinarians (AAHABV – which has a very small membership fee).

The best companion animal practices realize they "sell" only one thing: peace of mind for the client. They concurrently are a patient advocate and tell the client what is needed for the best of the pet, either of wellness or professional diagnostic concerns. The client is allowed to select from the list, they are allowed to "buy" what they think they can afford. Lesser cost alternatives are not offered UNTIL the client asks for lesser cost alternatives, but the "options" must be kept in perspective of lesser diagnostics, lesser response rates, or lesser probability of desired healthcare effects. Clients prefer to "buy" and hate being "sold" in most every occurrence, and a smart practice leader trains and rehearses the practice team to "sell" ONLY peace of mind, freedom from fears, or psychological comfort while allowing the client to "buy" products and services to their heart's content.

Dentistry is a common human-animal bond practice program . . . lack of oral hygiene is a cause of breaking the human-animal bond, as in so bad a breath that it would choke a horse. Restoring “puppy kisses” is the ultimate benefit of a dental prophy, but is seldom mentioned. When a practice starts to “grade” teeth, magic happens, especially with differential pricing. Dentistry is becoming a quotable commodity, so pricing is a community positioning action as well as client bonding action. The Holstrom, Frost Eisner dental text makes a clear differentiation between Tartar and Calculus, which I use here:

DISCLAIMER - in some areas of the USA, the above example prices are only 50% of the going rates. We usually recommend to phone or e-mail clients, where we have not assessed the community, that veterinary practices with a single dental rate peg their prices by using their current fee as the 2+ prophy rate, decrease by 25-33% for the grade 1+ prophy, increase by 50-75% for the 3+ oral surgery fee, and at least double for the 4+ oral surgery.

Behavior management is one form of HAB practice service; it is one of the hottest topics on the continuing education seminar circuit in recent years. A survey of Internet searches shows behavior management is the #2 reason for new clients selecting a practice (location was #1).

The primary problem is proactive behavior management services are a staff function as much as a professional service, and the staff members seldom get to attend the seminars. Obedience training is not behavior management, it is most often handler and location specific. HAB behavior management is teaching and rewarding the pet an appropriate family behavior by positive reinforcement. Allowing the client to "buy" these services is a client privilege most practices do not yet offer. Behavior management programs are easily initiated for dogs using the Gentle Leader head collar (usually provides “power steering” in less than 8 minutes when you understand that “release of pressure” is the animal’s reward of that device). The 65-page head collar booklet provides the techniques needed for behavior management, but the "caring" practice offers their nursing staff as “head collar fitters” at sale, and as trainers to help the client if they get stuck ($20 per appointment). This veterinary practice behavior management effort often leads to Puppy Clubs, Kitten Carrier Classes, Senior Clubs, and other client "social" programs (e.g., Guinea Pig Pig Out) which add to the practice bonding (and concurrently increases the client return rates -- and practice liquidity). In some cases, the practice supports a Pet Partner Program (Delta Society), and gains from the community good will and human interest media stories.

Behavior management is a potential practice area for staff to excel. Most are client education programs best done by trained staff members (e.g., house training, feeding, new owner orientation classes, etc.). In America, over 6 million animals a year lose their home and often their lives because of behavior problems. It is worse in many other countries. The veterinary practice team which helps prevent this "disposable pet" syndrome not only keeps clients, but gains positive recognition in the community. Recognition for helping animals is a marketing benefit to the practice without having to advertise or market routine services or products.

Nutrition is the ultimate human-animal bond for most clients. Clients like to feed their pet, because it makes the pet seem happy. We know that premium diets and quality nutrition will extend the active life of most companion animals, but we often forget to tell clients about “smaller stools” or “better smelling cat boxes” when feeding the highly digestible premium foods. Prescription diets should be treated like any other prescription, and be actively monitored by the paraprofessional staff at 2 to 4 week intervals; these can be “no cost” courtesy visits with the “nursing staff”, since purchase of goods usually accompanies a visit to the practice.

Changing “boarding” to a Pet Resort, or Canine and Kitty Camp, and changing “kennel kid” to animal caretaker, can change the atmosphere of the separation encounter. Using a Kong Toy for “yappie hour” (if they purchase a Kong Toy at guest check-in, a special feeding using the inside of the Kong Toy will be done at 5 p.m. daily, like a happy hour). When the pet goes home with the Kong Toy and “yappie hour” habit, when the client comes home from work and is greeted by a leaping bundle of fur, they can provide the Kong filled with food, and get changed into their doggy play clothes while the pet is occupied (P.S., Kong Toys are dishwasher safe, and almost indestructible, while not looking like anything in the home, except maybe the Michelin Man).

THE BOTTOM LINE

As a full time consultant, what I miss most about practice is “puppy breath”. Like most all veterinarians, our staff joins veterinary medicine because it is a “calling”; we know they do not join for the meager salary and benefits alone. When we can promote hospital staff as patient advocates, human-animal bond specialists, and “nursing” staff (a term the clients understand very well), we can reinforce the “warm fuzzy” aspects of this rewarding profession in their hearts and minds.

In a recessionary economy, clients stay home more, see their pet more, and will strive to fulfill “needs” while they postpone “wants”. Since 9-11-01, followed by the GFC (global financial crisis), practices which had been using the word “need” for healthcare have had greater client access; after 9-11, most had the best October and November in their history. Practices that clung to the nondescript “recommend”, or those that offer multiple options and expect client expertise to make rational decisions, had slower months than ever before; clients do not want to make choices when stressed, they want to be told what is needed by someone they trust.

Explore every client contact for those moments when the family-pet bond can be promoted. Listen to the Dr. Marty Becker “fear free” initiative being copied at many levels; brainstorm the concept with your staff to get real excitement going. Use every opportunity to acknowledge the important role the companion animal plays by providing their non-judgmental love in these times of stress and worry. Allow the practice staff members to select HAB areas of interest, help them develop a working knowledge of the subject material and healthcare delivery options, get them practice business cards with their new title (e.g., pain management advisor, veterinary dental hygienist, behavior counselor, nutritional advisor, etc.), and start to promote their interest and new knowledge as a client benefit. Celebrate the bond every day in every way!

July (mid-month) 2014

BEYOND PROBLEM SOLVING

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE

Dipomate, American College of Healthcare Executives

CEO, Veterinary Consulting International

DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com

Obstacles - those frightful things we see when we take our eyes off our goals. T.E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE

Some practitioners erroneously believe that solving immediate practice management problems is the best way to change productivity and performance. A better approach is to cultivate ideas whose application and impact range beyond the task of the moment. Overcoming inertia and getting things done rely on follow-through and breakthrough skills. BREAKTHROUGH SKILLS

As a team leader or a team member, you must first learn how to present your ideas in a comprehensive and enlightening manner: * COVER YOUR BASES. Before you show off your personal planning skills, make sure you are seen as doing a good job with your current responsibilities. If you don't have time to think beyond the immediate concerns on most practice days, delegate the more repetitive day-to-day responsibilities to dependable staff members. * NETWORK. Before you suggest an idea at a team meeting, try to get a feel for the other team members' interests and concerns. Know the problems they face and the solutions they have developed and address the issue at hand in terms that include their interests. * SEEK OPPORTUNITIES. View problems as opportunities to solve challenges. A strategic thinker sees multiple alternatives in events that others view as crises or failures. Nurture this attitude within the practice team.

* BE POSITIVE. Make your suggestions in a non-confrontational way. If your idea impacts others, soften your approach with phrases like "What are your thoughts on . . . ?" Remember, the staff within most every practice cares, they want to help, and their suggestions most always come with good intentions. Look for the caring intention BEFORE you evaluate the idea(s). * DON'T LIMIT YOURSELF. Do not hesitate to make suggestions that are not related to the bottom line. Clients must believe you care BEFORE they believe in your health care plan. The value of an idea to a practice is measured in quality of life as well as quality of care. Practice benefits can and should go beyond the cost-saving or profit-producing ideas.

FOLLOW THROUGH SKILLS Planning a project can be completely different from its implementation and far more difficult than ever anticipated. When projects stall, everyone becomes frustrated. Projects stall for many reasons, but the obstacles which initiate the stalling have some commonality. The first secret to proactively enhance the follow through is to recognize obstacles of your own making: * FANTASIES. The mind can envision how well a plan will work, and it is far happier than when overseeing the actual implementation hassles. You need to set the fantasy aside and get your hands dirty. Edison had a vision of how a light bulb should work but had to build over 1,000 of them to turn his vision into reality. Are you ready for 999 failures to become famous for your new ideas within the professional or client-based community? * FEAR OF FAILURE. Fear that results will fall short often cause us to let a project quietly die rather than live with poor results. Remind yourself that concrete results, even those that fall short of expectations, are far better than none at all. * INVISIBLE RUTS. A common pitfall is mindlessly following old habit patterns. We have learned from what went before, and know what works, but the practice plateau or lifestyle stagnation is caused by "non-change" rather than the pursuit of unique or new experiences. Ask if those old stale protocols are important and determine "why" if the tendency is to retain them. If the "why" is simply, "We have always done it this way," then bypass them, as necessary, to get things done. * COMFORTING MYTHOLOGIES. Don't fall prey to the slogans or comforts of tradition. Southern California community needs are different than the rest of the USA, suburban needs are different than small town rural America. Marketing gimmicks must be tailored to the community needs, not to the practice by some article or consultant who has not even been in your practice. If you believe "everything is fine as long as everybody is busy,” you might overlook the benefits of new projects. * EGOTISM. Thinking that your own intuition and insights are infallible cuts you off from your colleagues' ideas. Doctor, paraprofessional, or animal caretaker, it does not matter. Everyone has a mind and each mind has unique ideas to share, if harvested in a caring manner. Objectively review all suggestions, including your own, and implement the best. * FAILURE TO DELEGATE. You may be shouldering the whole burden because nobody else is as effective as you are . . . or because you don't want to share the credit when a project is done. Either way, you place the project at risk. Your odds of success increase greatly when you take on only the tasks that suit your abilities best and let others take on the rest. Train each person to a level of trust, then delegate the accountability for the outcome to them (not just the process). Let them improve the program(s). * INFLEXIBILITY. When an approach is not working, substitute something more positive. If your staff does not implement your ideas, ask them for alternatives. Let them develop unilateral plans and put those into action, then evaluate at 90 days for benefits. Never veto ideas just because they are not yours! Flexibility often requires taking a step backward, but ends up being more productive. * LOVE THE INTRIGUE. They are either with you or against you, right? Put aside petty intrigues and enlist everyone's help. A "them versus us" practice staff will never be a health care team. Only "we" can cause harmony and success. If you love intrigue more than progress, or you prefer to take credit and give blame rather than take blame and give credit, go into politics or the spy business.

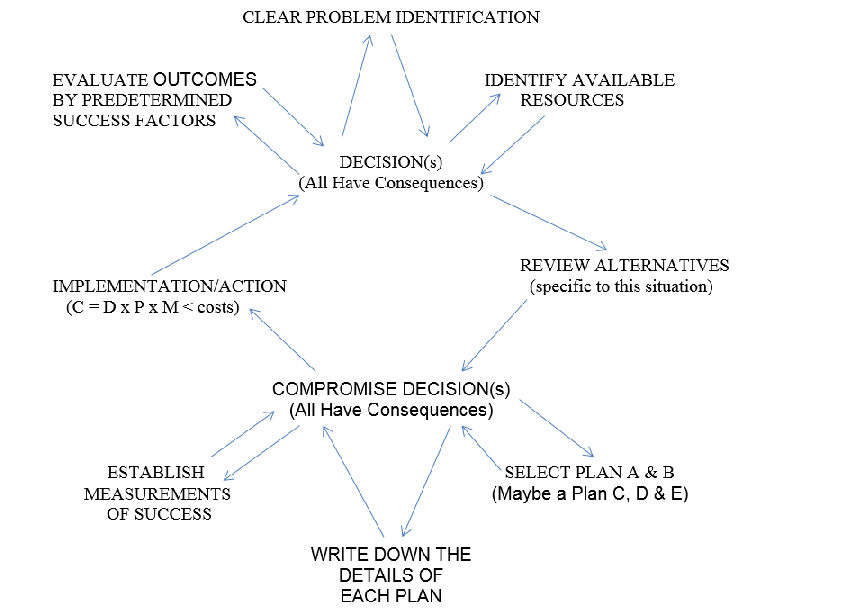

POWER UP FOR PROBLEM SOLVING In our daily routine of practice we rely upon habits to get the job done, but when we need a creative or innovative solution, many veterinarians don't know where to start. There are tools that teach creative problem solving. They don't give you genius, they simply pull out the genius within you. For those practices that do not have computers, or their computers are not friendly, the soft-cover texts, A KICK IN THE SEAT OF THE PANTS, or A WHACK ON THE SIDE OF THE HEAD, by Roger von Oech ($10.95 and $12.95 respectively, ISBN 0-06-09024-8 and 0-446-39158-1), provide exercises, stories, tips, and techniques to help you strengthen each of your own creative skills. The books are sold separately, but sometimes you can find them together with a deck of innovation cards, and the set is called a "WHACK PACK." These aids can be used to awaken these skills in your staff, since they are the best problem solvers we have. Then all you have to do is capture the great ideas from the flow of innovation. For those who have an ability to use a computer, friendly or otherwise, some of the more helpful software programs include: * IdeaFisher (approximately $495) contains two parts, the Idea-Bank which cross-references 60,000 words in 700,000 ways, and the Q-Bank which has 3,000 very specific questions designed to help you solve common business problems involving product lines. Available in IBM PC and Macintosh versions from Fisher Ideas Systems, 714/474-8111. * Namer (approximately $195) can help name products or services; it encompasses all kinds of product categories, but it is really best for naming health care products and high-tech services. It will combine root words related to those fields and come up with 200-300 possible names. Available in IBM DOS from Salinon Corp., 214/692-9091. * Idea Generator (approximately $195) combines seven brainstorming techniques to take your answers and reintroduce them as questions that force you to view a problem at a greater depth. Available in IBM DOS from Experience in Software, 415/644-0694. * Mindlink (approximately $499) uses a "mental gym" to warm up your mind with creative exercises, then the program runs you through a disciplined, step-by-step problem-solving activity. It forces you to remove yourself totally from the problem. Available in Macintosh from Synectics, 802/457-2025. * Inside Information (approximately $119) is a very new desktop accessory that contains 65,000 key words and their definitions and related concepts. Available in Macintosh and IBM DOS from Microlytics, 716/248-9150. New software to enhance creativity and innovation comes out every week. There are many other products coming available to help problem solving, innovation, and creative thinking for the average computer user. It is a smart idea to stop at the local software store and discuss your needs with a hacker on the staff. Do not buy the software product until you have booted it up yourself, fed in a current problem or idea, and see what the program can do for you. Not all programmers have the same logic tree as you, and very few understand health care delivery, much less veterinary medicine. These programs are just a logic tree that can be used by most decision makers who want assistance in innovative and creative thinking.

Problem Solving Process - VCI Veterinary Leadership Pocket Guide

DOING GETS IT DONE

When a project stalls, making a new beginning can provide the spark that lets a project catch fire. Inactivity leads to inertia, then the consultant must be called in to break the paradigms which formed the inertia. Picture your practice as a giant boulder resting on level playing field. Time has caused it to settle into a depression. With all the strength available, the boulder may only be moved an inch or two. If something isn't immediately added to the depression, the boulder will return to where it was. On the other hand, if something (e.g., an idea rock) was added to the void created by moving the boulder, it will not be able to return to the "old position" and just sit there. Each movement of the boulder allows another idea rock to be added to the temporary void. In time, the depression will be filled with new ideas and the boulder will be moved on the level playing field in whatever direction is needed, and with a lot less effort than ever before.

With or without an electronic computer, use your brain's natural logic for a five minute "boulder moving effort" when searching for the breakthrough or follow-through ideas. If you are stuck, agree with yourself that you will start to work on a task at a particular time and will continue for five minutes. At the end of the five minutes, determine if you want to continue another five. Make the same determination again, and so forth. This enables you to take focused action rather than view the project as behemoth and helps to build immediate response rewards. If all else fails, stop, relax, and remember the words of Isaac Newton:

"If I have ever made any valuable discoveries, it has been owing more to patient attention than to any other talent."

July 2014 VETERINARY PRACTICE IMAGES Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE Dipomate, American College of Healthcare Executives CEO, Veterinary Consulting International DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com

"He who knows much about others may be learned, but he who knows himself is more intelligent. He who controls others may be more powerful, but he who has mastered himself is mightier still." Lao Tsu

In a brainstorming session with other consultants, we looked at the average veterinary practice client cycle and counted the moments of truth that any practice could possibly influence. While all the ideas listed here will not fit every practice, the majority should. The challenge is to get the staff members to accept the responsibility to improve the image in each area they touch. They need to have pride in what they do, moment by moment, to affect these moments of truth. To establish that pride in performance is the challenge of leadership, but that is a different article! Most of the concepts discussed below are expanded in the new Blackwell/Wiley & Sons Press three volume text series, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice, and the sequel, Veterinary Healthcare Services: Options in Delivery. Look at these opportunities, and discuss them with your team:

Finding the Practice (you need to ask this question of ALL new clients to compile these answers) Social Media Yellow page ad Referral by friend/client Newspaper ad Community literature source Referral by out-of-state veterinarian Outdoor signage Ancillary pet supply referral Staff community service Community activities/Rotary/Scouting/women's clubs/government

The Initial Contact Phone for a price quote Phone for a service quote Phone for an appointment New Client Newsletter (mailed post-phone contact) Directions to the practice Stopping in for a tour Meeting a staff member out in the community Meeting the veterinarian at a community function Actual appointment hours offered

Arriving With the Pet Practice identification Direction signage for parking and entrance Parking lot appearance/tidiness/potholes/debris/droppings Access to the front door Entry ease and protection of pet from other patients Fear Factor enhancements Lighting/security Initial waiting room impression (smell, sight, sound) Access to the front desk Staff appearance Decor/odor/noise/cleanliness

Client Relations Specialist (Reception) Staff Courtesy/attentiveness Friendly/smiles Responsiveness/caring Pace/professional approach Phone techniques Gossip level Talk about pets/clients by name rather than condition Bond-centered Practice Approach Waiting time (a maximum of seven minutes) Amenities available Other clients entering and exiting (satisfaction)

Initial Client/Patient Movement Methods Appearance/uniforms/shoes/personal composure Personal hygiene/makeup/hair/breath/face hair Escort to consultation (examination) room Initial interview techniques Hands on pet within 30 seconds Fear Free aspects Nurse (Technician) appearance Body language/voice tone Staff competency Paraprofessional rapport Bond-centered Practice Approach Wellness examination Diplomas on wall (staff and doctors) Odor/cleanliness/noise

Veterinarian Initial Impact Appearance/personal composure Treatment of staff Respect for Outpatient Nurse comments Self-introduction Touching the animal Listening technique Body language/voice tone/rate of speech Terminology Explanation of consultation/examination/findings Patient advocacy/speaks of pet's needs/ensures client decides Bond-centered Practice Approach Empathy/concern for client's position (feelings and fiscal)

Consultation (Examination) Room Exit Summary of findings Staff Training to administer treatments Bond-centered Practice Approach Explanation of charges Prequalify each departure with the three Rs (recheck, recall, reminders) Escort to discharge Protection of animal during transit through hall/reception area

Discharge Actions Attentiveness at discharge/waiting time Discharge desk clutter/appearance Cleanliness/odor/noise Presentation of invoice/bill (consistency with estimate) Collection of fees (some practices have the nurse do this in consultation room) Dispensing medication Concern for client understanding Plan for next contact Bond-centered Practice Approach Establishing the three Rs compliance expectations (recall, recheck, remind) Privacy/courtesy/caring Literature offered to ensure family understanding

Post-discharge Follow-up telephone call by nursing staff Quarterly Informational Newsletters Sympathy cards/memorials for deceased pets Thank you correspondence Health Alerts (Volume 3, Building The Successful Veterinary Practice) Satisfaction surveys Reminders Recurring social media

Over one hundred moments of truth were listed above and the ability of the veterinarian to directly alter them accounted for only about ten percent of the total. The balance are done by staff, and the effectiveness is directly proportional to their level of training competence. Many practices have not yet discovered the value of team-based training, facilitated by veterinary-specific team-based trainers (e.g., see www.drtomcat.com). The amount of concern (training and rehearsal) exhibited by most veterinary practices does not equal the importance of these client impression opportunities.

Consider the moments of truth from the client's perspective. How many times can your staff, facility or practice methods offend their impressions of your practice before they are no longer a client? Conversely, when staff members feel proud of the practice and the healthcare delivery philosophy, every moment of truth is an opportunity to cement the doctor-client-patient bond.

In fact, as proven in most every service industry, how the operational managers and supervisors treat the staff will determine how the staff members treat the clients. When Carlzon asked the SAS headquarters staff what their "mission" was, it took three weeks for the team to decide it was "the movement of people." They closed the headquarters for about six months and took the client-centered service to the field and impressed every one of the 40,000 employees with their importance in the moments of truth. In two years, SAS went from a failing airline to one of the top three income producers in Europe; five years later it was failing again because the leadership appeared over-impressed with their initial effort and did not continue the client-centered emphasis on all programs. They forgot to look into the future and make the SAS employees responsible for changes in the future (there was NO continuous quality improvement). SAS lost money.

American examples do exist, like Marriott, Nordstrom, Worthington Steel, Federal Express, and American Airlines, but they are the exception rather than the rule. In industry and corporate America it has been called Total Quality Management (TQM). Authors like Juran, Deming, and Crosby have made their consulting fame by basing their approaches on reintroducing employee-based quality and pride factors to American corporations. They believe that when the employee puts pride into their daily effort, when they are empowered to make changes for the betterment of the team without first climbing the supervisory ladder for permission, the output will be perceived as quality. The successful veterinary practice empowers its staff to react and change to meet the client's needs. The staff member needs to have the freedom to commit resources without additional line item permission and to make the client perceive a caring staff and a quality healthcare facility. In human healthcare this concept is called Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI).

Assigning accountability to an employee (empowerment) must be accompanied by the needed authority, and these must be supported by job/task ownership. The staff member must think of the practice as "our practice/our hospital" at every decision point in the process. In the consulting business, we find that practice "luck" is usually directly related to the preparation of the staff to grab opportunity as it comes knocking. Where does your practice approach sit in the scheme of things when it comes to preparing your staff to grab the moment of truth and turn it to the practice's advantage?

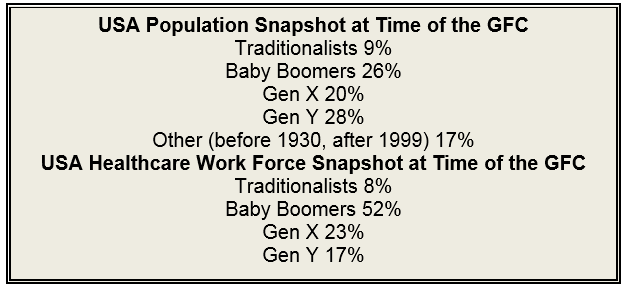

During the 1970s and 1980s, the veterinary client-centered trend in the United States inched away from client service in the quest for high-tech and personal specialization. However, the 1990s rediscovered the importance of service to the client, and client-centered service was rediscovered (and the AVMA even published an outstanding series of workbooks to help their members relearn this critical business facet, but very few used the AVMA texts as team-based training workbooks to establish an enhanced practice culture or solidify the practice philosophy). The new millennium and the GFC has demanded this facet for success be tailored to multi-generational expectations, including high tech savvy and proactive social media outreach!

The practice that best controls its respective moments of truth will become different from other practices in the mind of their community. These astute veterinary practices will succeed where others have floundered because practice quality and client impressions are communicated during the moments of truth and have very little bearing on the professional facts. They will become the leaders in the veterinary marketplace as we emerge from the GFC, using new millennium techniques.

June 2014 LEADING A MULTIGENERATIONAL PRACTICE TEAM Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LFACHE Dipomate, American College of Healthcare Executives CEO, Veterinary Consulting International DrTomCat@aol.com; www.drtomcat.com

You have to get different generations communicating so they can appreciate what each seeks and why, as well as identifying what they hold in common. Only through facilitated dialogue, where individuals feel listened to, can different generations within the practice team discover common ground. Tom Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, LHACHE

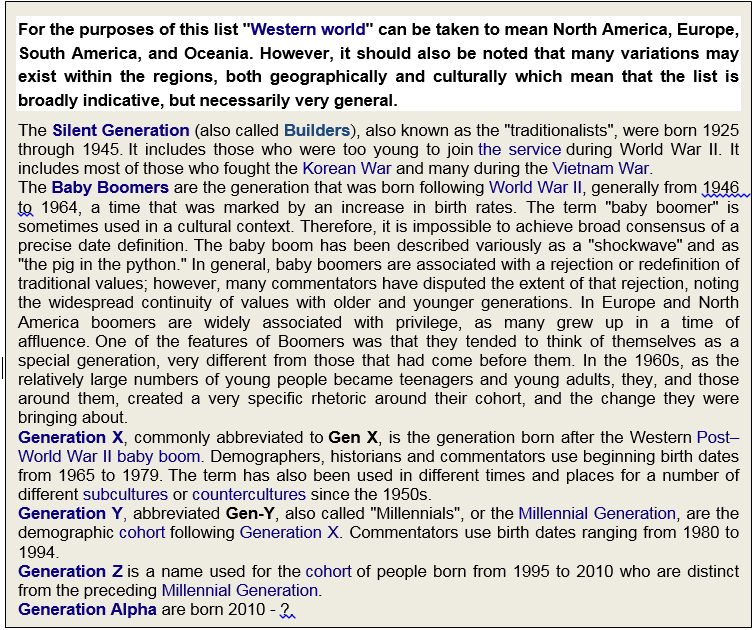

In very leadership course I have ever staffed, or developed, communication is defined as the "getting and giving of information." In most veterinary practice settings, the doctor has learned to talk "at" the staff members (that is how they were taught in school) rather than with them, and the ownership ensures the manager delegates processes rather than outcome tasks. This is now compounded by the generational differences seen within veterinary practice teams, which gives the organizational behavior and practice culture more stumbling blocks than answers. Currently, most multi-doctor veterinary practices have a staff comprised of four generations: traditionalists, baby boomers, Gen-X and Gen-Y. The difference in attitude and in value hierarchy among veterinary practice providers of different generations is so great that practice owners and younger staff often fail to even hear what the other is really saying. The older embers members of the staff believe the younger members have no work ethic, while the younger members of the practice team suggest the old timers should "get a life." But these obstacles can often be removed through facilitated dialogue that builds trust and enhances mutual understanding.

Traditionalist practice owners and Medical Directors were born at the end of World War II, and for them, veterinary medicine was a vocational calling. Their profession and self-identity are one in the same, and in their eyes are analogous to James Herriott, a priest, a rabbi, or other minister of the flock. Traditionalists respect hierarchy; join civic, fraternal, and professional organizations; are seldom computer literate, and would never imagine requesting reimbursement for being on call.

Baby boomer veterinarians learned from the traditionalists, so on the surface, they appear a lot like the guys who taught them their craft, often in ambulatory medicine settings. However, they work with a different set of motivation factors: the acquisition of material wealth is core to their practice approach. That attitude is particularly evident in the latter half of the baby boomer generation. Younger boomers are sometimes labeled the "Jones generation", as in "keeping up with the Jones." For the boomer veterinarian, failing to work generates feelings of guilt. The younger Baby Boomer veterinarians are loyal, do not fear taking on debt, do not tend to accept statements of authority, are not joiners, and are not likely to sacrifice personal pleasures for the good of the group.

Generation X are significantly different from traditionalists and baby boomers. For Generation X, managing time and balancing life are primary values; being part of a veterinary team is only a small part of the existence and self-identity. They are equally vested in life or lives outside the practice, and for that reason, prefer known shifts. Gen Xers are transactional and seek immediate stability, looking for what they can get for working the prescribed shift(s). They do not tolerate governance well, have a lack of trust in managers, supervisors/or even practice leadership; they are loyal to principles, not organizations.

THE NEW MILLENNIUM

A unique phenomenon occurred in the American workplace, especially in healthcares settings, as we entered the new millennium. before the new millennium, most leaders and employees shared a common generational attitude - they were most all part of the baby boomer generation. This congruence of generational attitudes clearly led to a more positive work environment and a more aligned and engaged work force, yet as we entered the new millennium, it all started to unravel.

Although Baby Boomers will continue being the primary practice owners and Gen Y associates, colleagues, and staff coming into their sphere of influence. The trend slowed when the GFC struck, and baby boomer retirements were postponed, but the economic restraints are changing again, in time, the generational shift will occur to Gen-X and Gen-Y values.